Half-Life: A Review in Futile Scientific Progress

Ah, Half-Life, that darling of the late ’90s PC gaming elite. A game where you, a silent MIT graduate in a glorified hazmat suit, spend your workday turning the government’s top-secret research facility into a multi-dimensional slaughterhouse. It begins with Gordon Freeman running late for work, which is the most relatable part of the game: a subway ride, a hangover from grad school debt, and then – oops – you’ve accidentally opened a rip in the fabric of reality. We’ve all been there.

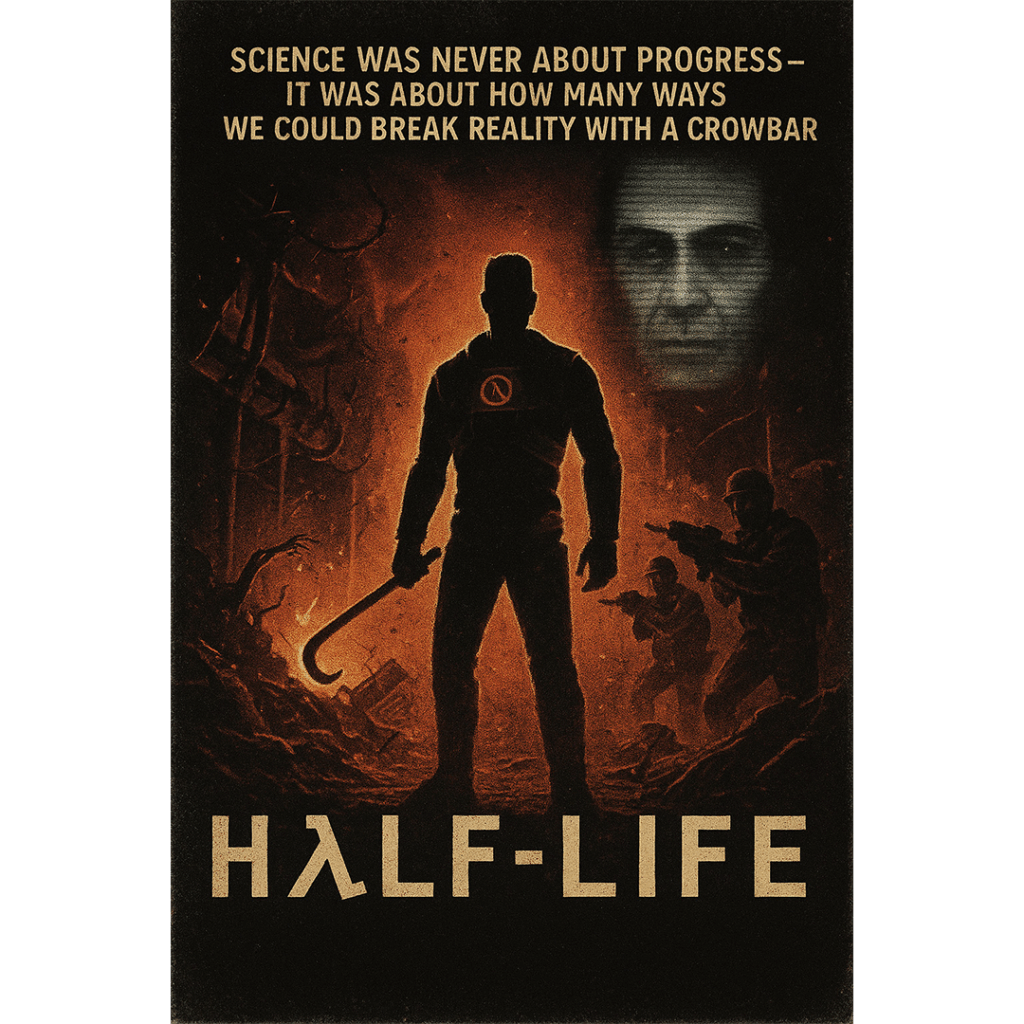

Valve wanted to immerse players in a cinematic experience, and they succeeded, if by “cinematic” you mean endlessly being screamed at by soldiers and aliens while lugging a crowbar like a psychotic maintenance worker. Freeman’s crowbar, in fact, is the most honest weapon in the game: an instrument of blunt rage wielded against glass, boxes, and whatever poor alien creature looks at you funny. It is the great equalizer, the proletariat’s Excalibur, a red pipe of destiny.

The genius of Half-Life is how it makes survival feel like an unpaid internship. You spend hours crawling through ventilation shafts, dodging malfunctioning elevators, and questioning whether OSHA even exists in Black Mesa. Meanwhile, marines try to gun you down for witnessing what is essentially a failed science fair project. And the final insult? You don’t even get a promotion, just a mysterious job offer from the G-Man, who sounds like your sleaziest uncle offering you “business opportunities. ”Half-Life isn’t just a game, it’s a grim corporate parable wrapped in alien ichor. It taught us that science is just curiosity weaponized, soldiers will happily kill their own tax dollars, and silence is the ultimate rebellion. Gordon Freeman doesn’t speak because he knows the truth: in the end, no one wants to hear your screams echoing through another government cover-up.

©2025 Project Mayhem, Inc.

All trademarks referenced herein are the properties of their respective owners.